Road congestion and crowding from rapid urbanization is making ground transportation increasingly difficult in city environments. As a result, the excitement over the development and imminent certification of electric vertical takeoff and landing (eVTOL) aircraft is palpable. As reported in the last issue of Aerospace Tech Review by Thom Patterson, the title of his article is self-evident: “The Electric Age is Already Here.” Urban Air Mobility (UAM) is the talk of the industry, even though it will likely be years until UAM operations become commonplace.

At the risk of dampening this excitement over UAM, a dose of reality is needed: The eVTOLs are all dressed up (or will soon be), but literally have no place to go. The eVTOL designs from original equipment manufacturers (OEM) like Joby, Lillium, Velocopter and Beta are impressive and exude the technological innovation we expect from bright young minds. But let’s face it, UAM will remain only an interesting aviation science project in our world if the required infrastructure is not built soon.

“Infrastructure” is a big and ominous word. It includes tangible things such as vertiports, passenger terminals, maintenance facilities, charging stations, communication equipment, sensors and spare parts. It also includes things that you can’t physically touch but are equally important, such as airspace design, approach and departure routes, dispatch services, satellite tracking, and weather reporting.

When it comes to UAM, patience is a virtue. Solving the infrastructure equation will require significant investment of time and resources and money. That said, three specific items should be addressed sooner than later if this industry wants to sustain relevant progress… let’s call them the “ABCs” of UAM infrastructure.

A is for Aerodromes

The fleet of eVTOL aircraft will need a suitable place to take off and land. The International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) refers to these places as “aerodromes”. In the UAM world, they are called “vertiports” and, according to Rex J. Alexander, this is the industry’s most pressing challenge to overcome for any UAM operation. “I think all the OEM’s woke up in 2020 and said: ‘holy cow, we don’t have an infrastructure.’” he told Aerospace Tech Review.

Founder and President, Five-Alpha

Alexander is arguably the smartest guy on the planet when it comes to heliports. He is the founder and president of Five-Alpha LLC, a global aeronautical consultancy specializing in helicopter and powered vertical lift infrastructure, operations, safety, training, and education. A 40-year aviation veteran and entrepreneur whose career encompasses military, commercial and general aviation, Alexander is a dual-rated pilot and licensed mechanic who serves as the primary infrastructure advisor to the Vertical Flight Society (VFS). He represents the interests of over 6,000 members to the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), ICAO, ASTM International and the aviation community writ large.

Alexander explained that there are currently no regulatory standards, fire codes, or building codes that address eVTOL landing areas. The impact of not having vertiport standards in place is a negative influence on individuals looking to invest in the future of UAM. Without documented and adopted standards and guidelines that state officials and local municipalities can point to, many agencies are very hesitant to issue any of the required permits to build vertiports.

To its credit, the FAA issued a Request for Information (RFI) two years ago to the eVTOL industry in an attempt to begin the process of establishing vertiport standards, but the response from industry was disappointing — likely because there has been limited eVTOL aircraft testing conducted in which OEMs have been willing to share the necessary performance data with the FAA. To develop effective and safe standards for vertiports, OEMs must begin to contribute performance data to this effort.

However, standards do exist for helicopter landing areas — heliports — and perhaps that’s a good place to start. According to FAA statistics, there are 5,824 civil heliports in the U.S, but only 58 are “public use.” The rest are designated as “private use,” which means that they are only available for use by the owner or those that are authorized by the owner. And, according to Alexander: “The FAA does not and cannot regulate private-use facilities.” He quoted from the first page of the FAA bible on heliport design guidance, FAA Advisory Circular AC-150/5390-2C, which states the following: “The FAA recommends the guidelines and specifications in this AC for materials and methods used in the construction of heliports. In general, use of this AC is not mandatory.”

“It’s probably time for a third category of heliport. Something for UAM operations.” Alexander warned. “You can begin with heliports, or with properly repurposed decks but you’re going to need to develop dedicated vertiports like what Lilium is planning in Orlando.” See image this page.

AC 150/5390 was first published 60 years ago and has been through 10 revisions with the most current being 2C, published in April 2012. But wait! Just last month, the FAA published a draft for a 60-day public comment of an updated version of AC 150/5390 — “revision 2D”. Unfortunately, the FAA seems to have doubled-down on its philosophy to not regulate vertiports, as indicated by this statement in Chapter 1 of the draft AC: “The guidance provided in this AC is limited to heliports and helicopter operations. This guidance does not address landing areas for or operations by vertical takeoff and landing (VTOL) aircraft or unmanned aircraft.”

“There needs to be a bridge that will allow eVTOL operations to occur at our current infrastructure for helicopters” Alexander suggested. “My hope is that the ASTM International standard being developed by their F38 committee can be that bridge.”

Nearly four years ago, ASTM began the process of developing consensus-based industry standards for vertiports, an effort that began with addressing unmanned aircraft systems (UAS). As expected, Rex Alexander is a loud and influential voice on this group, and he indicated that the ASTM standard’s formal release may occur soon.

“In moving forward, we will need performance data to properly develop a comprehensive FAA standard and are hopeful to bring as many OEM’s into that space sooner rather than later.”

Advisory Circular 150/5390 does go on to say that “… states, or other authorities having jurisdiction over the construction of other heliports decide the extent to which these standards apply.” In fact, many states, and local governments require adherence to the FAA heliport design guide to meet their compliance standards, so the non-mandatory FAA guidance can become “regulatory” by reference or incorporation.

“Another huge nut to crack is the Fire Code,” opined Alexander. Construction of vertiports will be subject to local fire codes, which will have significant impacts not only on the facility’s design, but also on its fire mitigation equipment and procedures. “The fire codes on the books now for heliports contemplate jet fuel. But what happens when you have a lithium ion battery that catches fire? Or hydrogen?”

Juggling yet another group effort, Alexander is actively involved with a committee at the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) that has begun the process of creating new standards for UAM-like operations. In May 2020, the NFPA-418 committee for Heliport Standards formed a task group to review new technologies and propose new language for the next draft of its standard. Alexander says that’s important because the International Building Code — another set of requirements — states that “Rooftop heliports and helistops shall comply with NFPA 418.”

Piling on yet another problem, the UAM industry must also consider the finite availability of electricity on the grid. Just lay out some charge plugs on the vertiport, right? Wrong. Alexander explained that OEMs are “designing around batteries up to 500 watt hours per kilogram, and these new lithium-metal batteries will need recharging after each flight,” but… with the nation’s power grid is already maxed out. “You’re going to need a new electrical power substation,” he said. “And with a cost of about a million dollars per mile to bring in power, it’s going to have to be located somewhere near the vertiport. If you think heliports are hated by the public for noise and safety concerns, start talking to them about putting in a substation.” Not to mention that substations typically take about two years to get a permit and two more years to build, plus any “lead time” to manufacture the highly specialized and sought-after components for substations.

B is for “Byways” in the Sky

The airspace around vertiports will need developed to accommodate safe and quiet approaches and departures, along with the routing to and from each vertiport. This airspace will form the “byways” needed for UAM operations.

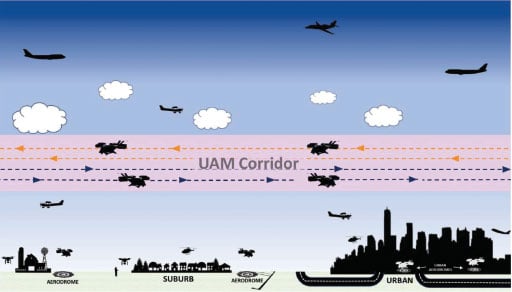

With the growing interest in the possibilities for UAM, key players in the industry, including NASA and the FAA, are working on a system for low altitude operations that will integrate into the current national airspace system (NAS). In July of last year, the FAA NextGen office released a “Concept of Operations” (ConOps) for UAM aircraft that focused on aircraft operating in “corridors” (see image below). In order for UAM to become a reality, it must be safe and scalable, which means individual states will need to overcome significant barriers to adoption and growth.

As depicted in the ConOps, the following principles and assumptions will be used when guiding the development of the UAM operating environment:

- UAM vehicles will operate within a regulatory, operational, and technical environment that is incorporated within the NAS.

- Any evolution of the regulatory environment will always maintain safety of the NAS.

- Airspace management will be structured where necessary and flexible when possible.

- Air traffic control (ATC) management will be conducted in compliance with a set of community developed and FAA-approved “community based rules” – more on that in the next section.

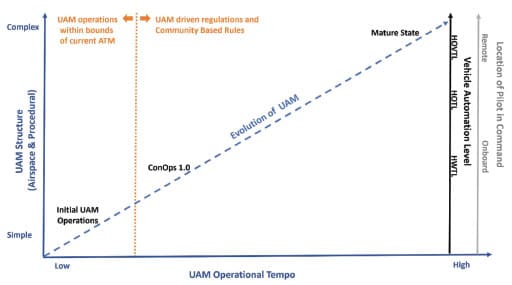

The FAA ConOps envisions the use of a “UAM Corridor” which is defined as “An airspace volume defining a three-dimensional route segment with performance requirements to operate within or cross where tactical ATC separation services are not provided.” The FAA expects to scale up UAM operations through the use of these corridors in which aircraft will operate without direct involvement from the current ATC system. Initially, the ConOps focuses on evolving current helicopter routes into UAM corridors (see image below)

However, according to Jay Merkle, the Executive Director of FAA’s Unmanned Aircraft Systems Integration, in comments he made at last month’s Vertical Flight Society’s eVTOL Symposium: “The corridor concept is not a scalable concept for high-volume, so we will have to figure out some way other than corridors. Corridors are great for aircraft that need to transit airspace infrequently, understanding that the traffic in that area typically gets priority. Those constructs just don’t work for … high-density UAM.”

The ConOps document provides an initial roadmap for how the U.S. might achieve high-volume urban air taxi operations while maintaining the safety of the NAS. Developed with input from NASA , industry and community stakeholders, the document outlines a “crawl-walk-run” approach. It assumes that initial UAM operations will use eVTOL aircraft that are certified to fly within the current regulatory and operational environment with an onboard pilot. Aircraft operating within the corridors will still have pilots onboard, but will also be equipped to exchange information with other users of the corridor in order to deconflict traffic without relying on ATC. Eventually, the FAA anticipates the system evolving to the point where UAM corridors form a complex, high-volume network through which UAM aircraft will fly autonomously (see image next page).

According to Merkel, airspace integration is a key issue facing UAM. “I think this is going to be a big challenge for this community. The traditional operators in this airspace will not easily yield their positions, and there will have to be some detailed discussions on how to do scale operations…”

FAA graphic.

C is for Collaboration … and Communities

Interrelated to the “Aerodrome” and the “Byways” concepts is perhaps the most critical challenge to overcome in order to jump start UAM operations — “Collaboration.” Support for a broader urban planning capability relies on extensive collaboration with another “C” word — “Communities” – that build and live in the urban context. States will need to identify stakeholders to collaborate with, such as Public Private Partnerships, regulatory requirements, operations over people, modernizing infrastructure, etc. The key players in this dance should include OEMs, regulators, technology innovators, state & local leaders, and investors in the community who can discuss on-demand aviation for smart cities in order to create a new future for air transportation.

As mentioned in the previous section on “Byways,” the key players will need to agree upon “Community Business Rules” which are defined as a collaborative set of UAM operational business rules developed by the stakeholder community. These rules may be set by the UAM community to meet industry standards or FAA guidelines when specified, and they will require FAA approval.

Last year, Mark Moore, co-founder of Uber Elevate, spoke at the Vertical Flight Society’s 76th Annual Forum. “Right now, we’re working a great collaboration with the FAA, NASA and our OEM partners on coming up with an infrastructure requirements document.” Moore said Uber is aiming to start flying its partners’ first eVTOL aircraft between 2023 and 2024. That’s a great incentive to push for an infrastructure that does not yet exist. (see image 10).

At last year’s World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, U.S. Secretary of Transportation Elaine Chao, gave a speech that encapsulated the sentiment of UAM collaboration and community. She said, in part: “To be fully deployed, UAM technology must first win the public’s trust and acceptance. UAM systems will be flying directly over and landing near neighborhoods and workplaces. So, it is imperative that the public’s legitimate concerns about safety, security, noise and privacy be addressed.” She challenged the industry “to step up and educate communities about the benefits of this new technology and win their trust.”

S is for Services

The small “s” at the end of “ABCs” could stand for “services” — a topic that is too comprehensive and complex to be addressed here — it deserves its own article. While not quite as an urgent need as the three aforementioned “ABC” topics, a safe and prolific UAM operation will require flight tracking services, dispatching, and, eventually, the 800-pound elephant in the room known as Unmanned Traffic Management or UTM. The need for these services will grow exponentially once the UAM market proliferates. The FAA’s UAM ConOps addresses this with many pages and diagrams about the need for “providers of services for UAM.” These “PSUs” will be utilized by UAM operators to receive/exchange information via a network that enables safe, efficient operation within the UAM corridors without involvement by ATC.

Another critical service will be to provide weather information to UAM operators. This is already a challenge for helicopter operations, especially for Helicopter Air Ambulance community that conduct off-airport scene operations. Even with today’s array of 2,278 certified weather reporting systems in the Continental U.S. — a whopping 97.5% of this area does not have an FAA-approved weather source as per FAA’s Part 135.213 air taxi regulation because each of the reporting stations is valid only within a 5-mile radius.

What to Do NOW?

So, what should the industry do NOW and in the near term to accelerate infrastructure development so that the UAM pie in the sky has a place to roost? “We need to focus on getting POLICY to catch up to the technology” says Alexander. “We need to educate ourselves about what policy exists today and what needs to be developed. Hire someone who knows what policy is. Look and see what is going on in this space with ASTM and the FAA. Make comments during public comment periods. Anybody can comment.”

He also implores folks interested in UAM to get more involved. The eVTOL OEMs, FAA, trade associations, state authorities and other interested parties should actively participate at the numerous forums. “For example, I would highly encourage your readers to attend the Vertical Flight Society’s upcoming 4th Workshop on eVTOL Infrastructure to be held virtually from March 2–4.”

Good advice for those who want to grease the skids for UAM operations to arrive in a few years, rather than a couple of decades.